5 de April de 2022

Foodborne viral illnesses: preventive measures

For years, food contamination through viruses has been considered the main source of infectious diseases via food (Rodrigo A et al. 2007). However, most foodborne viral illnesses go unreported because people do not seek medical attention when they experience the effects (e.g., mild gastroenteritis, the most common symptom of foodborne viral illnesses). In addition, the detection of viruses in food is difficult because many of them cannot be cultured in the laboratory and their detection requires advanced molecular techniques.

But viruses, like bacteria, can contaminate food and cause illness. The big difference is that viruses do not multiply in food because outside of a host they are totally inert. They need to be inside a host in order to replicate and be harmful. Thus, the resistance of viruses to the extracorporeal or environmental medium will be of fundamental importance in how viral diseases are transmitted.

In the case of foodborne viral illnesses, these are mainly caused by enteric viruses. These viruses are transmitted by the fecal-oral route and can therefore potentially be found in any food that has been contaminated with fecal matter at any stage of the food chain.

What are viruses?

Strictly speaking, viruses are not living organisms. They are obligate intracellular parasites incapable of self-replication and range in size from 20 to 300 nm. In the appropriate host they reproduce by infecting its cells, where they parasitise the subcellular machinery, using it to their own advantage to produce more viral particles, ending with the destruction of the host cell.

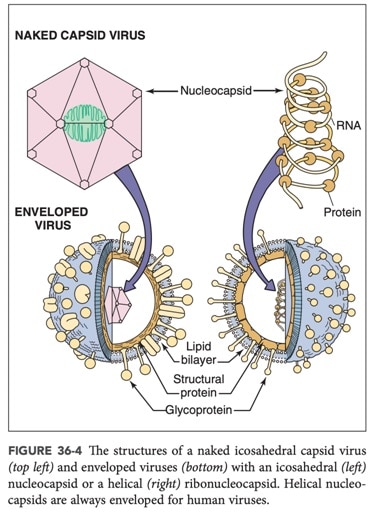

In their simplest forms, viruses consist only of a nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) surrounded by a protein coat called a capsid. The association of the capsid with the nucleic acid forms the nucleocapsid. This nucleocapsid is the structure that corresponds to a naked virus. In other cases, the virus consists of the nucleocapsid and an envelope composed of lipids, proteins and glycoproteins, a structure that corresponds to an enveloped virus. Enveloped viruses acquire the envelope when they leave the host cell by budding (Cooper, 2009).

Murray PR, Rosenthal KS, Pfaller MA. Medical Microbiology. Eighth Edition. (2016), Elsevier Inc.

Classification of viruses

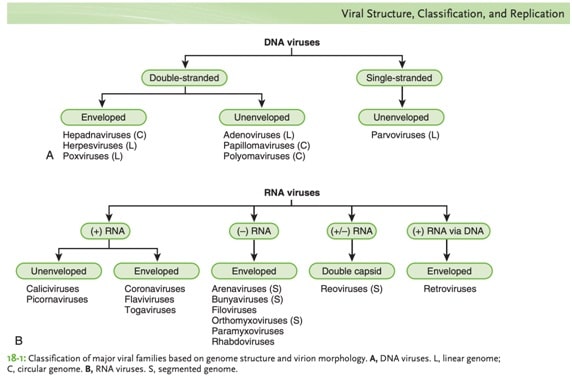

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses is responsible for their classification. The criteria for defining a family are the type of nucleic acid (RNA or DNA), genome structure, mechanisms and site of replication, presence or absence of envelope, capsid symmetry (helical, icosahedral or complex), site of assembly of viral particles (nucleus or cytoplasm) and way of exit from the host cell (Carballal G et al., 2014).

Rosenthal KS and Tan MJ. Rapid Review Microbiology and Immunology. 3rd Edition. (2011). Mosby, Inc., an affiliate of Elsevier Inc.

Enveloped and naked viruses

The presence or absence of an envelope determines the resistance of viruses to the external environment (desiccation, ultraviolet light, pH, ionic medium…) and this is of fundamental importance in the way viral diseases are transmitted.

Enveloped viruses are easily inactivated by lipid solvents (ether, chloroform, bile salts, detergents…). Therefore, for their transmission, direct person-to-person contact or contact through inert elements is required. In contrast, naked viruses are resistant to these solvents and can also be efficiently transmitted by the fecal-oral route as they retain their infectivity in water and can resist the acid pH of the stomach and the action of bile salts (Carballal et al., 2014).

Foodborne viral illnesses

Foodborne viral diseases are caused by various enteric viruses that require particularly low infectious doses and are transmitted by the fecal-oral route. If we consider the number of food outbreaks associated with this type of virus, the most prominent from the perspective of viral food safety are the Norovirus (Caliciviridae family), which causes gastroenteritis, and the Hepatitis A virus (Picornaviridae family), which causes acute hepatitis. Both are non-enveloped (naked) viruses, have RNA genomes and are surrounded by a protein coat with an icosahedral structure.

Foods that present a higher risk of being contaminated by enteric viruses include bivalve mollusks, vegetables consumed raw, berry fruits and any food susceptible to contamination from poor hygienic handling by food handlers.

Hygienic measures to avoid contagion.

The main form of virus transmission is person-to-person contact or contact via contaminated inert surfaces. As mentioned above, enteric viruses, which are highly resistant to the environment, can also be transmitted by the fecal-oral route.

Thus, the vast majority of virus infections can be prevented with proper hygienic measures, such as frequent hand hygiene, cleaning and disinfection of contaminated surfaces and proper food handling (avoiding direct handling with hands, proper cooking and washing and disinfection of vegetables).

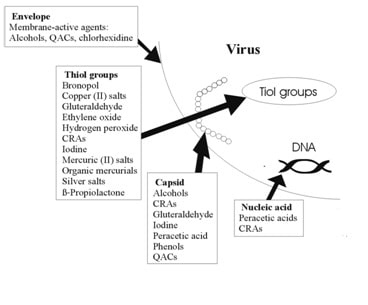

At Proquimia we have a wide range of disinfectant products, based on a great variety of biocidal active ingredients (quaternary ammoniums, chlorine, alcohols, trialkylamines, glutaraldehydes, etc.), which allow the application of different mechanisms of action for the inactivation of the different types of existing viruses.

Action of biocides against viruses. (Araújo P. et al. 2011)

The disinfectant products available for surface and environmental disinfection, as well as for hand antiseptic treatment, are duly registered within the existing legal framework, defined by the following regulations:

- Regulation (EU) No. 528/2012 on biocidal products (known as BPR-Biocidal Products Regulation)

- Royal Decree 3349/1983 of 30 November, approving the Technical-Sanitary Regulations for the manufacture, marketing and use of pesticides.

The above regulation establishes that the virucidal efficacy of products must be demonstrated through the EN14476 standard. This standard tests against 3 viruses: Poliovirus type 1 (Picornaviridae family), Adenovirus type 5 (Adenoviridae family) and Murine norovirus (Caliciviridae family), all of the non-enveloped type. Of the three viruses, Poliovirus is far more chemically resistant than the other two. Therefore, the standard states that if a product passes the tests only for Norovirus and Adenovirus, but not for Poliovirus, it is considered to have “limited virucidal activity”, which means that it is effective against all enveloped viruses, plus Adenovirus, Norovirus and Rotavirus.

Therefore, the design and implementation of an adequate Cleaning and Disinfection (C+D) plan is essential to avoid the risk of contagion. Proquimia’s Technical Department specialists can help you design customised C+D programmes, advise you on identifying and assessing risks at critical contact points to avoid cross-contamination between employees, and provide operator training and awareness on good hygiene practices.

Bibliographic references:

AESAN. 2011. Informe del Comité́ Científico de la AESAN sobre contaminación vírica de los alimentos, con especial énfasis en moluscos bivalvos, y métodos de control. Online. [Fecha de consulta 08/04/2020]. Disponible en: https://bit.ly/34qfgx4

Araújo, Paula & Lemos, Madalena & Mergulhão, Filipe & Melo, Luis & Simões, Manuel. (2011). Antimicrobial resistance to disinfectants in biofilms.

Carballal G, Oubina JR. Virología medica. 4a ed. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Corpus Libros Médicos y Científicos, 2014.

Cooper GM, Hausman RE. The Cell: a Molecular Approach (2009) 5th edition. ASM Press. Washington, DC; USA

International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses ICTV. [Internet]. Virus Taxonomy: The Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. [Fecha de consulta: 15/04/2020]. Disponible en: https://bit.ly/3bh3Jmf

Laboratoire des Médicaments Vétérinaires, Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Pêche, Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 1995. [Internet]. [Fecha de consulta: 14/04/2020]. Disponible en: https://bit.ly/34HypL0

Rodrigo A et al. Virus entéricos en alimentos: Incidencia y métodos de control. Profesión veterinaria. [Internet], [Fecha de consulta: 08/04/2020]. Disponible en: https://bit.ly/2RszdOz

Rosenthal KS and Tan MJ. Rapid Review Microbiology and Immunology. 3rd Edition. (2011). Mosby, Inc., an affiliate of Elsevier Inc.

Rutala WA, Weber DJ. Selection of the Ideal Disinfectant. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. Cambridge University Press; 2014;35(7):855–65.

Author: Agustí Capdevila

Do you want more information?

We help you

In accordance with Regulation 2016/679 (GDPR) the basic information on personal data protection is provided below:

- Data controller: PROQUIMIA, S.A.

- Purpose of processing: Managing the sending of information, resolving queries and/or collecting data for possible business relationships.

- Legal Basis: Consent of the person concerned

- Recipients: No data will be transferred to third parties, unless this is legally obliged.

- Rights: Access, rectification, deletion, opposition, limitation, portability and presentation of claims.

- Additional information: Additional and detailed information on Data Protection can be found on our website: Privacy policy